U.S. Rep. John Larson, left, sent a video message of support to Josh Serrano and the Clay Arsenal Renaissance Apartments tenants.

The bottom level of the famous hierarchy of needs, postulated by Abraham Maslow in the 1940s, is physiological. The most basic needs of human beings have to do with the survival and safety of the body. Air, water, food and shelter are often seen as the key parts of this base layer of Maslow’s pyramid. Developments of history and politics have carved up which of these needs is provided by the state and which is covered by the private sector. The area of housing is a tricky one for those in the nonprofit sector. Homes are too expensive for those at the community level to build from scratch, and housing problems are not easily fixed by holding community fundraisers and donation drives, as for food and clothing.

The remedies for want and need of housing often exist in the world of politics and policy, requiring public investment of time, energy and money. In Hartford, one of the greatest places of need in terms of adequate housing, the Christian Activities Council has been working for decades on the problem.

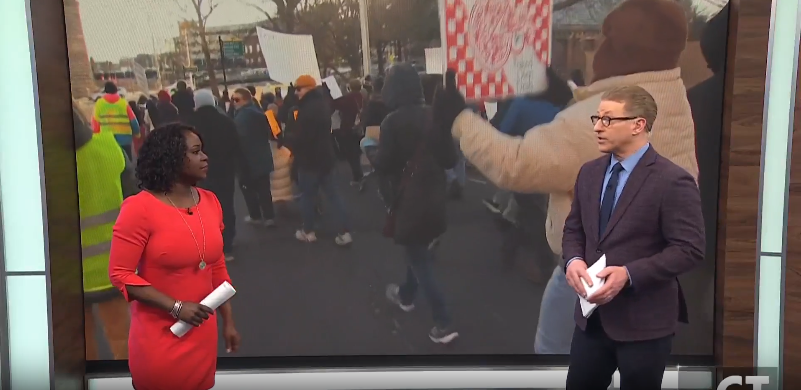

At a December meeting and rally organized by CAC, the full organizational capabilities of the group and those it works with were on display, as residents of the Clay Arsenal Renaissance Apartments (CARA) gathered with city leaders at the Union Baptist Church on Main Street to let the public and assembled media know about their struggle and to hold local politicians to account. Since July, CARA residents have been organizing against their landlord, Emmanuel Ku, who they say maintains properties with rodent infestations and chronic mold.

The event illustrates CAC’s work in two ways. First, it places those most affected at the center of its organizing practices. The informational session and press conference were almost entirely directed by residents of the buildings. Josh Serrano, who lives in a Ku-owned, mice-infested building on Main Street, takes the podium to detail his struggles and what he describes as intimidation by the landlord.

“The CAC has had our backs from day one, and always follows the tenants’ lead. They don’t make a move without our say,” Serrano says.

CAC’s work is also demonstrated by the manner in which Hartford Mayor Luke Bronin’s presence is treated. As he takes the podium, Bronin is held to task by CAC members and the tenants’ organization. Serrano sets a firm rule: Bronin must answer either “yes” or “no” to a series of questions posed by CAC’s organizer, the Rev. Ashley “AJ” Johnson. The questions are pointed, requiring the mayor to commit to particular enforcement actions and transparency procedures. It’s a rare sight to see a city mayor compelled to answer the kind of “yes” or “no” questions one might expect from a television debate moderator, but instead posed by community leaders on behalf of low-income tenants. From the perspective of the tenants, Bronin passes this test with flying colors, committing to every action the tenants ask of him.

The organizational acuity and forcefulness of the CAC perhaps owes itself to the length of time the group has been around: since 1850 to be exact, when it was founded as the Young Men’s Missionary Society out of “concern for the plight of the poor and new immigrants in Hartford,” according to the group’s website.

Since the 1950s, housing has been a major focus of advocacy and organizing for the CAC, and since the late 1980s the group has had a formal relationship with the Hartford Housing Authority focused on constructing more affordable housing in the city. What was clear on this night at the Union Baptist Church, however, was the extent to which the CAC was not in the driver’s seat, and the way it ceded its authority to the tenants for whom it advocates.

“I found my voice and a new family in the organizing process, and I’m proud of that,” Serrano says. “I’m ready to fight.”